Masterpiece Conversations | Ancient Art

Pic: Charles Ede, London.

Adam M. Levine is the Edward Drummond and Florence Scott Libbey Director of the Toledo Museum of Art (TMA), Ohio. He was previously Director and CEO of the Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens in Jacksonville, Florida, before which he worked in a senior management role at TMA, where he was responsible for all curatorial activities relating to ancient art.

Charis Tyndall is Director of Charles Ede, London, one of the world’s leading dealerships for works of ancient art from Egypt, Greece and the Roman Empire. She is a member of the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art (IADAA) and treasurer of the Antiquities Dealers’ Association (ADA).

What first sparked your interest in this field?

Charis Tyndall: I became interested in antiquities when I was very young. We’re talking about the origins of art, really, of when man started to build things and create idols; I think that can grip you as a child very easily, because it’s about basic human needs. I lived in Edinburgh until I was four or five years old: one of my favourite things at the weekend was visiting the museum on Chambers Street [now the National Museum of Scotland] and going to the ‘ancient peoples’ section, as it was known. Even as a child, you could glimpse all these ancient customs that you could sort of understand, but the display also felt very magical. Although I didn’t formally study Ancient History until university, I started learning about mythology when I was very young – and my fascination with it is also one of my earliest memories.

Adam M. Levine: For me, it’s very much the same story, and it’s what all the data suggests about museum visitation too: if you go early, you become a museum visitor. I’m a New Yorker and I was very fortunate to have parents who took me to the Met, where we would spend most of our time in the Greek and Roman, and Egyptian departments. I think there’s something captivating about the age of the things to someone so young – an almost incomprehensible amount of time – coupled of course, with mythology, which is a bit romanticised in the popular culture that you’re exposed to as a child. I certainly fell victim to the charm of those mythical origin stories from lands far away and times long ago – they have all the ingredients of the type of stories that young children love.

The moment I knew I was going to specialise in ancient art – I’ll admit it – was in high school when I read The Da Vinci Code. That book is what it is, but the thing that really struck me was a scene where the characters talk about how the Gospels ended up in the New Testament. It’s effectively pseudo history about the First Council of Nicaea, which isn’t accurate, but which first suggested to me as a 16-year-old that religion could be constructed. When I got to Dartmouth College, there was a course on early Christian art history, which I decided to take. It was taught by an important Byzantinist called Kathleen Corrigan, and after that I enrolled on all of her courses – on Byzantine art history, on Roman art history. That’s how I came to specialise in late Roman art. If you find a professor who you love, you should take every course they teach.

The Classic Court, Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio. Photo: courtesy Toledo Museum of Art

How did those formative interests become professional pathways?

CT: About halfway through my degree in ancient history and classical archaeology, I realised that there aren’t a lot of avenues to go down if you want to continue studying those fields. I initially worked for Charles Ede after my first year of university, but it took me a couple of years to recognise that I could make a career focused on antiquities in a commercial context – whether researching the objects, which is what I did first, or actually being on the buying and selling side.

AL: Museums were always interesting to me; when I matriculated, I immediately sought out a work opportunity at the Hood Museum of Art, which is on the campus at Dartmouth. (I was fortunate that I was able to study art history for three or four years at high school, and to continue with it at college.) Museums seemed an opportunity to leverage my passion for the subject for maximal impact, as the volume of people who come through them greatly exceeds the number that you might teach in a classroom.

CT: And of course then it’s not just the history, but how we learn about the history from the objects that are left behind…

AL: I totally agree. Where a historian thinks about historiography, we think about the social biography of the object – the traces and how this thing was used, how it lived, and what that tells you about the culture that manufactured it and the cultures that preserved it to this day.

Installation view of ‘The Berlin Painter and His World’ at Toledo Museum of Art, 2017. Photo: courtesy Toledo Museum of Art

Which recent developments in research and exhibition-making on ancient art have you found most inspiring?

AL: To be honest, I’m not sure that exhibition making and exhibition design for ancient material has caught up with the scholarship. I still think the narratives we tell tend to be at the societal level, as though societies were homogenised groups. There’s a lot of work to do, using primary evidence and deep readings of objects, to try to recreate the perspective of the individual and to understand the variability of interpretations and perspectives, even in antiquity. I expect to see more of that in the future.

CT: In my work, exhibition making has been more about displaying objects at art fairs, but in the context of Covid-19 we’re learning to become more technologically minded. For museum collections, I think that technological advances will transform how people are able to study and research objects – just the opportunity to zoom in on vase paintings in high resolution, or start spinning a vase virtually as though you were turning it in your hand, will do wonders for the understanding of these objects. The wider visibility and accessibility of objects through digital catalogues is transformative.

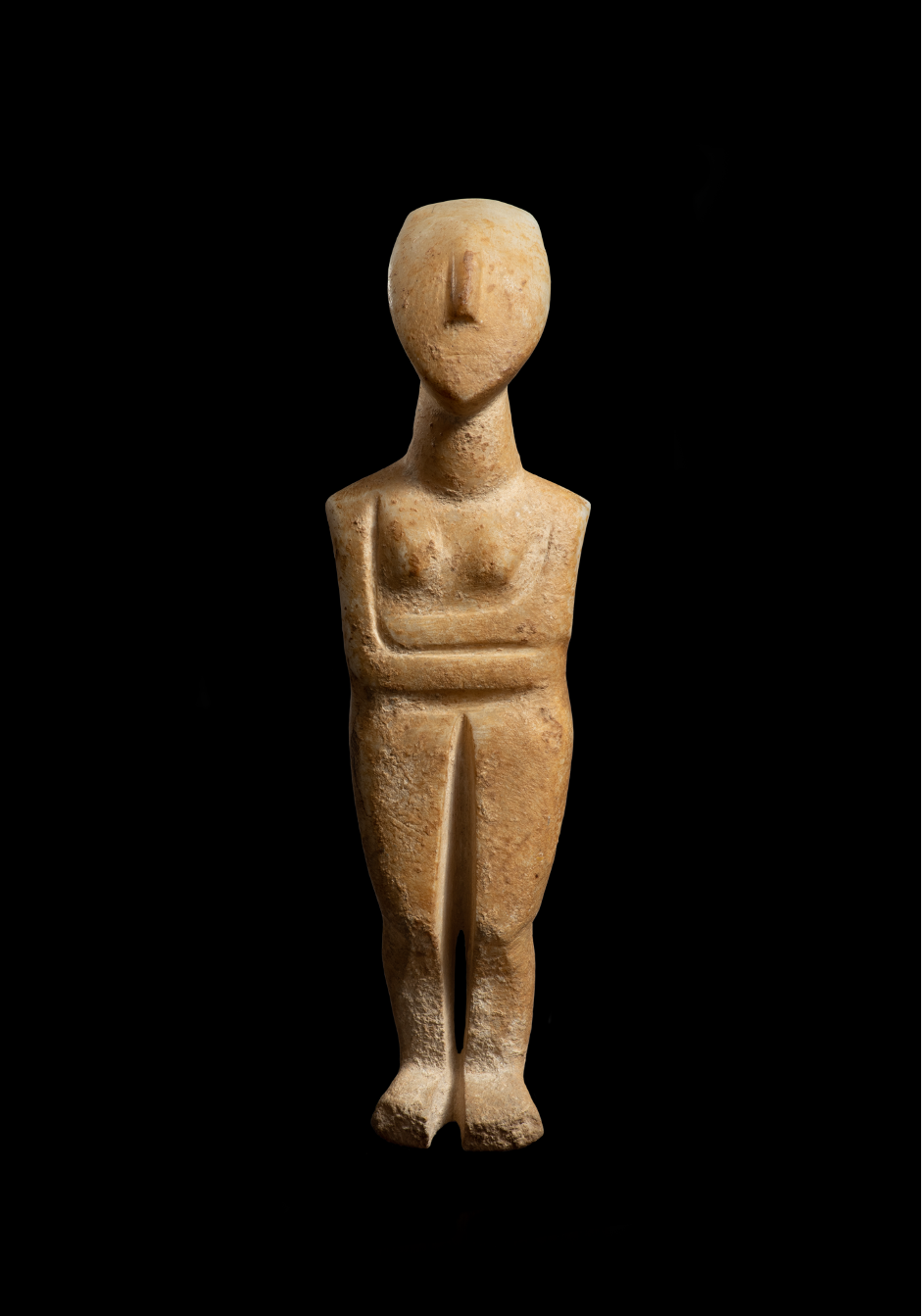

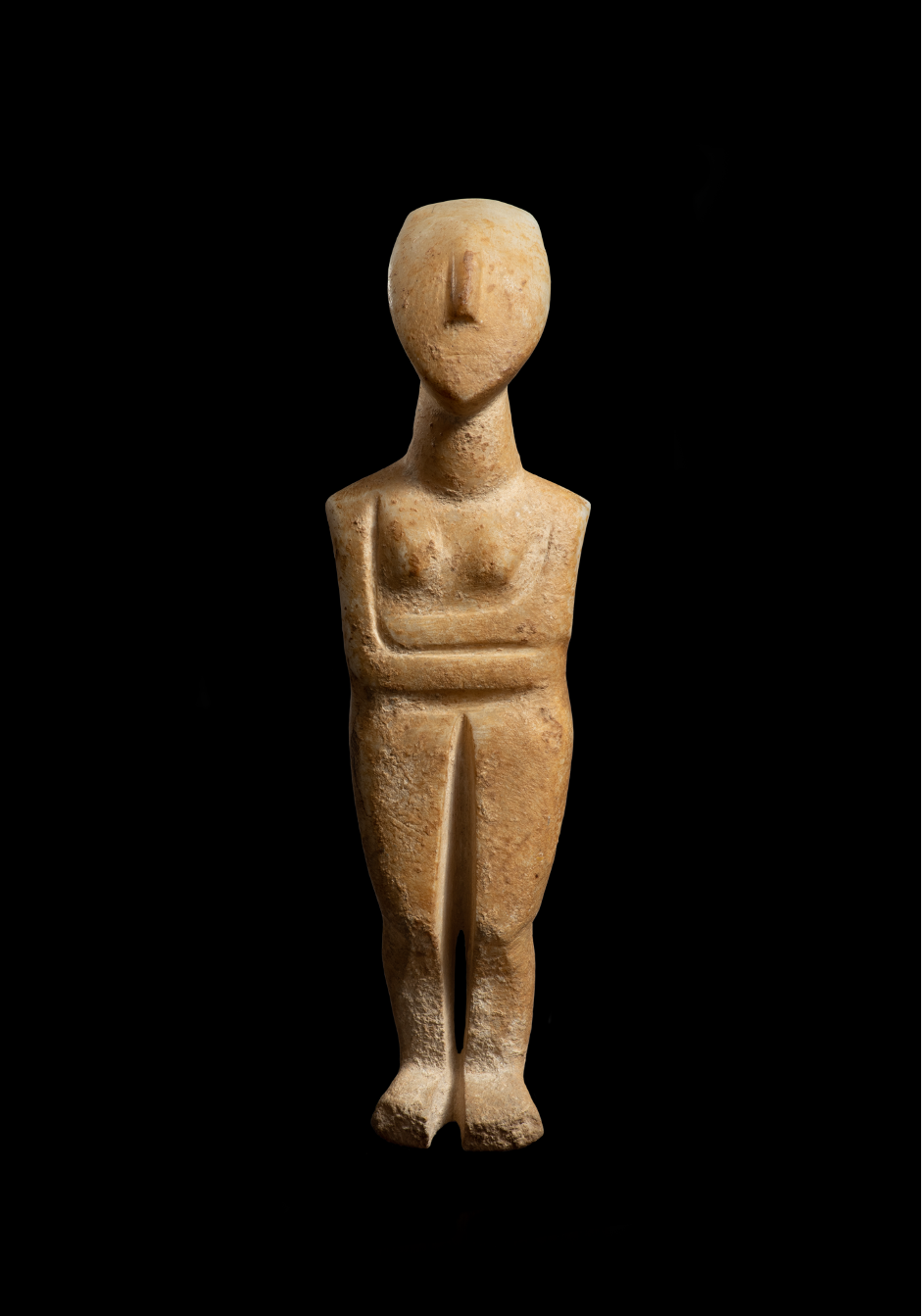

Cycladic Female Figure, Early Spedos, c. 2,600 BC, attributed to the Bent Sculptor. Charles Ede, London

Could the information that accompanies objects be better communicated, particularly when it comes to provenance and condition?

AL: In terms of communicating information in the museum, the challenge is that in the physical space we’re still bound by the material reality of object labels, and how they relate to people’s attention spans. I think the answer for providing richer access to information lies in the digital domain, and it is incumbent on us as institutions to think about how we relay that information appropriately, and make it part of the interpretive experience. Provenance, or ownership history, is what gives an object its life. It ought not to be considered as a dry, legalistic thing; it’s actually part of understanding the object.

CT: In the art market in general, there’s a lot more transparency than there used to be, including more readily available provenance. But there are still people who think that provenance and where an object originates from are one and the same thing. It’s vital that we explain who has owned things previously, which countries objects have moved through and which collections they’ve been part of, and how that might change our interpretation of them. The more information we can give people, the better they will understand the field.

With condition, I still find it frustrating that in some museums and galleries restoration histories aren’t always well communicated. Visitors would learn more if they knew which bits of an object were from the 17th century, which from the 18th century, and which had been done really cleverly last year. I think it would help, in both the commercial and the museum worlds, if we could be more transparent about condition without someone having to ask about it – that can be a bit of a barrier, as people don’t want to sound ignorant.

AL: The only footnote I’d add is that different collections are trying to do different things, and tell different stories about the ancient world. Some museums, such as the Kimbell, are aiming to have just a few exceptional objects on display. But certainly, if you have an encyclopaedic collection, then interpreting previous ownership and what various campaigns of restoration tell you about the history of the object may be very meritorious approaches. The sub-field of vases leads the way on this, I think, in terms of communicating conservation histories.

What more could the antiquities trade do to dispel misinformation about the field?

CT: The trade should lead by example. It’s important that we keep reassessing how we’re treating these objects, and what questions we’re asking of them – just as collectors and admirers of them will be doing. National laws haven’t always kept up with ethics, which is why the rules and guidelines set by trade associations are so important. The ADA and IADAA are constantly scrutinising the market and saying, this is what we should and shouldn’t be doing – particularly when it comes to objects that originate from countries that may have recently experienced conflict or other types of duress.

Will there always be controversies when it comes to how material from the ancient world is handled and displayed? Can you imagine a future in which various political, institutional and commercial interests are fundamentally reconciled?

AL: I can only answer from a very personal point of view. My view of the conversation is that we tend to start it halfway through. A really good place to start encouraging consensus – and bear in mind consensus is not unanimity – is to remember that the first part of the conversation is that everyone involved values antiquity and wants it to be preserved, including those things that have not yet been excavated.

We tend to have conversations that start with past deals and end with future preservation, and we also have conversations about ethics, morals and nationalist legal regimes. (I don’t mean ‘nationalist’ in a way that’s loaded, but that the boundaries of nation states are used to determine ownership, when those boundaries are modern constructions that don’t map perfectly on to ancient boundaries.) There’s a lot to untangle, but we need to have conversations that don’t begin by vilifying the other.

CT: That rings very true. We all have the same goals of preserving antiquity to better and further understand it, and of gaining pleasure from objects that were created to enhance people’s lives and continue to do so.

AL: We need to grasp the opportunity to generate authentic trusting relationships, to create consortia and get all the different stakeholders around the table more frequently. Perhaps museums could be the sites for convening those conversations.

CT: Greater collaboration can happen on a smaller scale, too. If Adam comes on to our stand at an art fair, he’ll impart his knowledge on the objects, we’ll discuss them, and we’ll talk about the art market. That’s important, too.

Roman statue of a draped goddess, 1st century BC–1st century AD. Charles Ede, London

Has it become more challenging for museums to acquire ancient art?

AL: In general, sure, because you’re contending with the perceptions of the space that we’ve been talking about. We can no longer think of this field outside that context, nor should we: museums operate in the public trust, so it’s vital to make sure that when we’re acquiring things we fulfil the highest ethical standards. Curators and directors have to educate their trustees and decision makers about the careful due diligence that needs to be done. There are still unbelievable collecting opportunities in the field of ancient art that have impeccable provenance.

CT: I hope we can get to a place where good provenance is as much of a given as authenticity…

AL: It’s important to say that the absence of evidence is not the same as evidence of absence. If an object appears without a known ownership history, that doesn’t mean that with research you can’t uncover it. The culture around recording ownership was different in the past. You can actually unearth tremendous value by using research skills to recover that ownership history; that adds a dimension to our understanding of the object and of the cultures that preserved it for us.

Provenance as both a means and end of research, then. Have the priorities of private collectors changed noticeably in recent years?

CT: How people collect has definitely evolved, even in the last 15 years. Our clientele used to largely consist of people who collected quite academically – who wanted every shape of black-glazed vessel, for instance, or a bust of every important Roman emperor. We now find that more people are buying things that are visually arresting, that they’re collecting works of art, not just antiquities. Those collectors don’t always apprehend all the questions they ought to ask before they make an acquisition, since they aren’t already immersed in the field; that’s why it’s so important to buy from someone reputable, or at a fair like Masterpiece, where the questions that needed to be asked have already been asked by the vetting committee.

AL: There’s definitely a growth in contemporary art collectors who are looking for striking objects. And It’s great that antiquities dealers – Charles Ede among them – are juxtaposing antiquities with other art forms. The best booths I’ve seen at art fairs aren’t just pseudo formalism; they’re displays that create legitimate intellectual connections.

Adam M. Levine is the Edward Drummond and Florence Scott Libbey Director of the Toledo Museum of Art (TMA), Ohio. He was previously Director and CEO of the Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens in Jacksonville, Florida, before which he worked in a senior management role at TMA, where he was responsible for all curatorial activities relating to ancient art.

Charis Tyndall is Director of Charles Ede, London, one of the world’s leading dealerships for works of ancient art from Egypt, Greece and the Roman Empire. She is a member of the International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art (IADAA) and treasurer of the Antiquities Dealers’ Association (ADA).

What first sparked your interest in this field?

Charis Tyndall: I became interested in antiquities when I was very young. We’re talking about the origins of art, really, of when man started to build things and create idols; I think that can grip you as a child very easily, because it’s about basic human needs. I lived in Edinburgh until I was four or five years old: one of my favourite things at the weekend was visiting the museum on Chambers Street [now the National Museum of Scotland] and going to the ‘ancient peoples’ section, as it was known. Even as a child, you could glimpse all these ancient customs that you could sort of understand, but the display also felt very magical. Although I didn’t formally study Ancient History until university, I started learning about mythology when I was very young – and my fascination with it is also one of my earliest memories.

Adam M. Levine: For me, it’s very much the same story, and it’s what all the data suggests about museum visitation too: if you go early, you become a museum visitor. I’m a New Yorker and I was very fortunate to have parents who took me to the Met, where we would spend most of our time in the Greek and Roman, and Egyptian departments. I think there’s something captivating about the age of the things to someone so young – an almost incomprehensible amount of time – coupled of course, with mythology, which is a bit romanticised in the popular culture that you’re exposed to as a child. I certainly fell victim to the charm of those mythical origin stories from lands far away and times long ago – they have all the ingredients of the type of stories that young children love.

The moment I knew I was going to specialise in ancient art – I’ll admit it – was in high school when I read The Da Vinci Code. That book is what it is, but the thing that really struck me was a scene where the characters talk about how the Gospels ended up in the New Testament. It’s effectively pseudo history about the First Council of Nicaea, which isn’t accurate, but which first suggested to me as a 16-year-old that religion could be constructed. When I got to Dartmouth College, there was a course on early Christian art history, which I decided to take. It was taught by an important Byzantinist called Kathleen Corrigan, and after that I enrolled on all of her courses – on Byzantine art history, on Roman art history. That’s how I came to specialise in late Roman art. If you find a professor who you love, you should take every course they teach.

The Classic Court, Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio. Photo: courtesy Toledo Museum of Art

How did those formative interests become professional pathways?

CT: About halfway through my degree in ancient history and classical archaeology, I realised that there aren’t a lot of avenues to go down if you want to continue studying those fields. I initially worked for Charles Ede after my first year of university, but it took me a couple of years to recognise that I could make a career focused on antiquities in a commercial context – whether researching the objects, which is what I did first, or actually being on the buying and selling side.

AL: Museums were always interesting to me; when I matriculated, I immediately sought out a work opportunity at the Hood Museum of Art, which is on the campus at Dartmouth. (I was fortunate that I was able to study art history for three or four years at high school, and to continue with it at college.) Museums seemed an opportunity to leverage my passion for the subject for maximal impact, as the volume of people who come through them greatly exceeds the number that you might teach in a classroom.

CT: And of course then it’s not just the history, but how we learn about the history from the objects that are left behind…

AL: I totally agree. Where a historian thinks about historiography, we think about the social biography of the object – the traces and how this thing was used, how it lived, and what that tells you about the culture that manufactured it and the cultures that preserved it to this day.

Installation view of ‘The Berlin Painter and His World’ at Toledo Museum of Art, 2017. Photo: courtesy Toledo Museum of Art

Which recent developments in research and exhibition-making on ancient art have you found most inspiring?

AL: To be honest, I’m not sure that exhibition making and exhibition design for ancient material has caught up with the scholarship. I still think the narratives we tell tend to be at the societal level, as though societies were homogenised groups. There’s a lot of work to do, using primary evidence and deep readings of objects, to try to recreate the perspective of the individual and to understand the variability of interpretations and perspectives, even in antiquity. I expect to see more of that in the future.

CT: In my work, exhibition making has been more about displaying objects at art fairs, but in the context of Covid-19 we’re learning to become more technologically minded. For museum collections, I think that technological advances will transform how people are able to study and research objects – just the opportunity to zoom in on vase paintings in high resolution, or start spinning a vase virtually as though you were turning it in your hand, will do wonders for the understanding of these objects. The wider visibility and accessibility of objects through digital catalogues is transformative.

Cycladic Female Figure, Early Spedos, c. 2,600 BC, attributed to the Bent Sculptor. Charles Ede, London

Could the information that accompanies objects be better communicated, particularly when it comes to provenance and condition?

AL: In terms of communicating information in the museum, the challenge is that in the physical space we’re still bound by the material reality of object labels, and how they relate to people’s attention spans. I think the answer for providing richer access to information lies in the digital domain, and it is incumbent on us as institutions to think about how we relay that information appropriately, and make it part of the interpretive experience. Provenance, or ownership history, is what gives an object its life. It ought not to be considered as a dry, legalistic thing; it’s actually part of understanding the object.

CT: In the art market in general, there’s a lot more transparency than there used to be, including more readily available provenance. But there are still people who think that provenance and where an object originates from are one and the same thing. It’s vital that we explain who has owned things previously, which countries objects have moved through and which collections they’ve been part of, and how that might change our interpretation of them. The more information we can give people, the better they will understand the field.

With condition, I still find it frustrating that in some museums and galleries restoration histories aren’t always well communicated. Visitors would learn more if they knew which bits of an object were from the 17th century, which from the 18th century, and which had been done really cleverly last year. I think it would help, in both the commercial and the museum worlds, if we could be more transparent about condition without someone having to ask about it – that can be a bit of a barrier, as people don’t want to sound ignorant.

AL: The only footnote I’d add is that different collections are trying to do different things, and tell different stories about the ancient world. Some museums, such as the Kimbell, are aiming to have just a few exceptional objects on display. But certainly, if you have an encyclopaedic collection, then interpreting previous ownership and what various campaigns of restoration tell you about the history of the object may be very meritorious approaches. The sub-field of vases leads the way on this, I think, in terms of communicating conservation histories.

What more could the antiquities trade do to dispel misinformation about the field?

CT: The trade should lead by example. It’s important that we keep reassessing how we’re treating these objects, and what questions we’re asking of them – just as collectors and admirers of them will be doing. National laws haven’t always kept up with ethics, which is why the rules and guidelines set by trade associations are so important. The ADA and IADAA are constantly scrutinising the market and saying, this is what we should and shouldn’t be doing – particularly when it comes to objects that originate from countries that may have recently experienced conflict or other types of duress.

Will there always be controversies when it comes to how material from the ancient world is handled and displayed? Can you imagine a future in which various political, institutional and commercial interests are fundamentally reconciled?

AL: I can only answer from a very personal point of view. My view of the conversation is that we tend to start it halfway through. A really good place to start encouraging consensus – and bear in mind consensus is not unanimity – is to remember that the first part of the conversation is that everyone involved values antiquity and wants it to be preserved, including those things that have not yet been excavated.

We tend to have conversations that start with past deals and end with future preservation, and we also have conversations about ethics, morals and nationalist legal regimes. (I don’t mean ‘nationalist’ in a way that’s loaded, but that the boundaries of nation states are used to determine ownership, when those boundaries are modern constructions that don’t map perfectly on to ancient boundaries.) There’s a lot to untangle, but we need to have conversations that don’t begin by vilifying the other.

CT: That rings very true. We all have the same goals of preserving antiquity to better and further understand it, and of gaining pleasure from objects that were created to enhance people’s lives and continue to do so.

AL: We need to grasp the opportunity to generate authentic trusting relationships, to create consortia and get all the different stakeholders around the table more frequently. Perhaps museums could be the sites for convening those conversations.

CT: Greater collaboration can happen on a smaller scale, too. If Adam comes on to our stand at an art fair, he’ll impart his knowledge on the objects, we’ll discuss them, and we’ll talk about the art market. That’s important, too.

Roman statue of a draped goddess, 1st century BC–1st century AD. Charles Ede, London

Has it become more challenging for museums to acquire ancient art?

AL: In general, sure, because you’re contending with the perceptions of the space that we’ve been talking about. We can no longer think of this field outside that context, nor should we: museums operate in the public trust, so it’s vital to make sure that when we’re acquiring things we fulfil the highest ethical standards. Curators and directors have to educate their trustees and decision makers about the careful due diligence that needs to be done. There are still unbelievable collecting opportunities in the field of ancient art that have impeccable provenance.

CT: I hope we can get to a place where good provenance is as much of a given as authenticity…

AL: It’s important to say that the absence of evidence is not the same as evidence of absence. If an object appears without a known ownership history, that doesn’t mean that with research you can’t uncover it. The culture around recording ownership was different in the past. You can actually unearth tremendous value by using research skills to recover that ownership history; that adds a dimension to our understanding of the object and of the cultures that preserved it for us.

Provenance as both a means and end of research, then. Have the priorities of private collectors changed noticeably in recent years?

CT: How people collect has definitely evolved, even in the last 15 years. Our clientele used to largely consist of people who collected quite academically – who wanted every shape of black-glazed vessel, for instance, or a bust of every important Roman emperor. We now find that more people are buying things that are visually arresting, that they’re collecting works of art, not just antiquities. Those collectors don’t always apprehend all the questions they ought to ask before they make an acquisition, since they aren’t already immersed in the field; that’s why it’s so important to buy from someone reputable, or at a fair like Masterpiece, where the questions that needed to be asked have already been asked by the vetting committee.

Roman bust of Hermarchus, 2nd century AD. Charles Ede, London

AL: There’s definitely a growth in contemporary art collectors who are looking for striking objects. And It’s great that antiquities dealers – Charles Ede among them – are juxtaposing antiquities with other art forms. The best booths I’ve seen at art fairs aren’t just pseudo formalism; they’re displays that create legitimate intellectual connections.

Please check your email and activate your account

Something went wrong